With tech giant Amazon being involved in a slew of Twitter battles over the past week, it has unravelled multiple issues which demand immediate attention. In a bitter response to Senator Elizabeth Warren’s tweet that accused Amazon of using “armies of lawyers and lobbyists” to evade taxes, the Amazon News account was quick to respond with jabs at the senator.

Dave Clark, CEO of Amazon’s consumer operations, responded in a similar fashion to Bernie Sanders’ visit to Bessemer to support the workers’ union drive. Sanders didn’t reply to the tweets directed at him, but Rep. Mark Pocan, a Democrat from Wisconsin, responded by charging Amazon with union-busting and worker mistreatment. Pocan pointed out reports that workers had to pee in bottles to keep up with their workloads.

While the battle ended in an apology from Amazon, the fashion in which the corporation took digs at these politicians was “uncharacteristically spiteful and petty”. This raises questions about how powerful these big corporations are, and their ability to openly suppress looming complications surrounding workers’ mistreatment and tax evasion.

However, workers and unions across the world are protesting relentlessly for their rights, leaving Amazon no choice but to shift priorities from winning Twitter battles to taking serious action on the ground. Whether it is workers in the USA, Italy, Germany or India, they have all demanded better working conditions, which they claimed have worsened over the course of the pandemic.

Indian Federation of App-based Transport (IFAT) workers said in a press note released on Wednesday that delivery staff of Amazon were making around INR 20,000 a month before the national lockdown last year, but that earning has now dropped to INR 10,000 following updated payment structures, which pay them INR 15 per delivery as opposed to the previous commission of INR 35.

In Bengaluru, a few delivery partners reported that they were not given protective equipment like masks, during the pandemic. Balaji (name changed), a 26-year-old delivery partner for Amazon, says “Amazon has not given me a single mask or sanitiser this year. I had to buy the mask myself. Doing work for them is very risky.” Meanwhile, Amazon continued to express how they “prioritise the health and safety of [their] delivery partners.”

However, these issues regarding workers’ mistreatment are affecting delivery personnel across firms. As acknowledged by Amazon in their recent blog post which was a response to Rep. Pocan, they mentioned how poor working conditions are “a long-standing, industry-wide issue” which are “not specific to Amazon”.

“Before the lockdown, I would earn around Rs 900 a day, by delivering about 60 parcels. During the lockdown, I earned nothing,” said Ramesh (name changed), a 40-year-old ‘delivery partner’ for Myntra. Unfortunately, Ramesh reflects the story of several delivery workers across India, who have faced severe income losses after the COVID-19 lockdown in March of 2020.

Since most of these delivery workers are ‘independent contractors’ who work for digital platforms like Amazon, Myntra and Swiggy, they are legally not considered as employees of the firms. They are not entitled to minimum wages and other benefits like insurance and pension which are offered to workers within the firms. Over these stated concerns, delivery workers like Ramesh have to pay for fuel and bike repair costs out of their own pockets, pulling down their actual incomes below minimum wage. According to a recent study by the National Law School of India University, this figure stands at Rs 65.80 per hour in Karnataka.

Bhavani Seetharaman, a policy researcher studying labour and technology, explains how the protests by Zomato workers in Bengaluru, in September 2019, successfully brought this issue to the state’s notice. “These protests specifically led to the labour department in Karnataka attempting to create legislation for gig workers in the state.” The issues covered under the legislation include health insurance in the event of accidents and fair wages.

Seetharaman continues, “While this was the start of a much-needed legislation, post the pandemic these dialogues have stopped.”

Needless to say, post the pandemic is when this legislation was needed the most.

Ajit (name changed), a 36-year-old delivery partner for Swiggy, points out how Swiggy has reduced the per-delivery rate since March. “Earlier, I used to get Rs 15 per delivery, and now I get paid Rs 12.” He explains how this change has immensely impacted his finances. “I can’t afford to pay for my children’s school fees this year. It doesn’t make sense to pay Rs 3000 for 4 hours of online class a month, when we need that money for food and rent.”

When workers try and speak up about such issues, they face harsh consequences from their employers. Ramesh explains, “Myntra has cut the per-delivery rate from Rs 15 to Rs 11 this year. When some workers tried to complain about this [to their managers], they were assigned fewer deliveries in a day. Few others were even fired.” This points towards a larger issue of lack of agency, that most gig workers are subjected to.

While the platforms tout delivery work as ‘flexible’, implying that their ‘delivery partners’ can choose the number of hours they work, this is often not the case. Ramesh continues, “The per-delivery rates are so low, we are forced to accept any and all orders that we are assigned, at any time of the day.” Despite this, Ramesh still falls short of the income needed to pay rent and other utilities. This has led him to take up a second job as a delivery partner for Amazon.

The platforms also deny their delivery partners other benefits like health insurance and pension. While Swiggy has promised insurance to its workers in case they test positive for COVID-19, Ramesh seems sceptical. “We did not sign any contract for this, nor were we told about how much money we would get [in the event of testing positive for COVID-19.]”

To address these issues, Seetharaman says that the way forward is “To define gig workers as workers of the formal economy.” This would give them the same protections as workers in other sectors, such as minimum wages and health insurance.

She points out that the recent Code on Social Security is a starting point for such legislation. This is because it has at least begun to define gig workers, and discuss their need for social securities. However, the Code does not make it compulsory for platforms to provide these social securities to their workers.

As the size of the gig economy (delivery services) continues to increase during the pandemic, and cases of wage slashing continue, there is an imminent need for stronger labour legislation. As Ramesh puts it, “Without us [delivery workers], these companies cannot continue to function. How is it fair that they get richer this year, while we struggle to survive?”

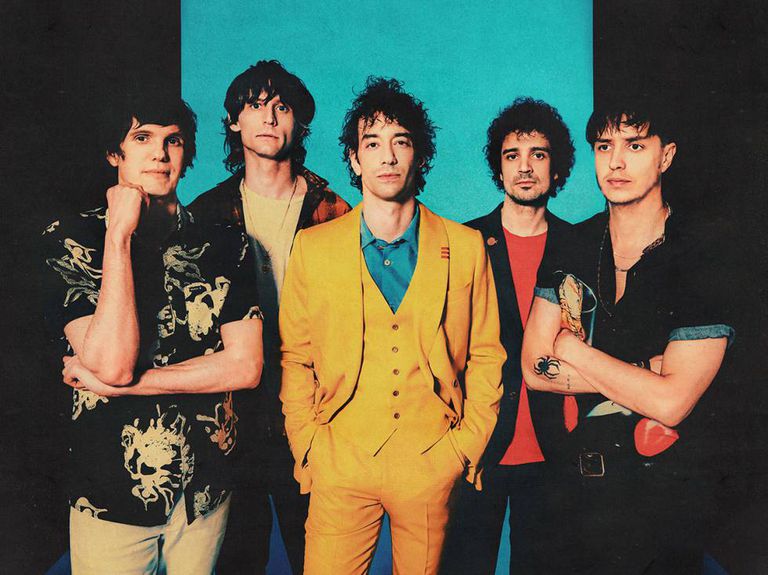

Image credits: Forbes

Samyukta is a student of Economics, Finance and Media Studies at Ashoka University. In her free time, she enjoys discovering interesting long-form reads and exploring new board games.

Rohan Pai is a Politics, Philosophy and Economics major at Ashoka University. In his free time, you’ll find him singing for a band, producing music and video content.

We publish all articles under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noderivatives license. This means any news organisation, blog, website, newspaper or newsletter can republish our pieces for free, provided they attribute the original source (OpenAxis).