Females in India aged six and above spend nearly seven hours a day on household chores while men contribute a measly three. The findings of a 2019 survey highlight the crucial role that 160 million homemakers play in the well-being of their households. Post-pandemic, only 7% of men lost their jobs as compared to 47% women, a significantly larger chunk. Predictions that fewer women will return to work, while employment levels for men will recover to pre-pandemic levels make such statistics jarring.

Interestingly, homemakers from various backgrounds have begun transforming their vast skillsets into potential businesses to help their families financially. From providing tiffin services in Patiala, selling candles in Chandigarh, and designing macrame wall hangings in Mumbai, homemakers are setting up an assortment of businesses. Their success is aided by Instagram and other platforms that are actively promoting small businesses.

Government policy has begun to recognize homemakers as a part of the workforce and as significant contributors to the national economy. Homemakers are being promised financial tools to venture into the sphere of small businesses with notional incomes in compensation-related cases, and sums of money from political leaders as an attempt to recognize their daily work and encourage entrepreneurship.

However, in an age where online education on platforms such as Coursera and Indian portal Swayam aim to equip individuals with diverse skills, is providing homemakers with kitchen-based business opportunities and interest-free loans enough? Or is there a need for digital upskilling to exercise these opportunities?

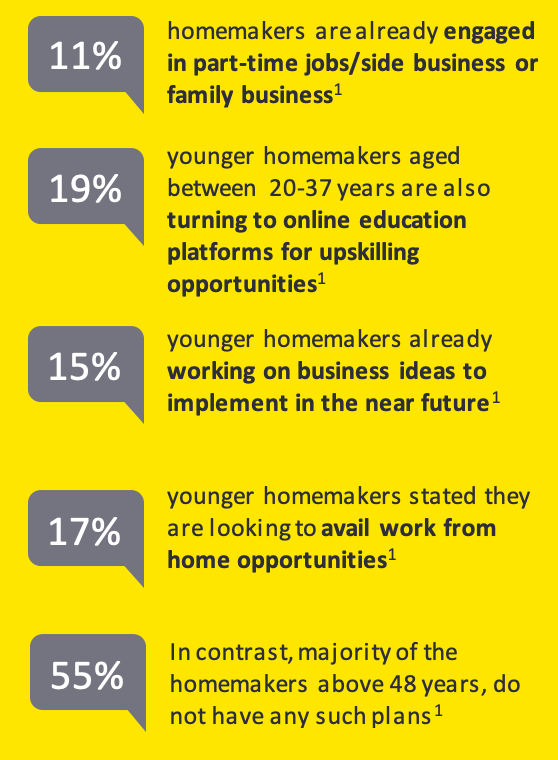

As per a recent study assessing the lives of homemakers from Tier-1 cities, 19% of homemakers aged between 20-37 years frequently take up online courses to upskill themselves, while around 15% are in the process of ideating and developing their business strategies. However, 55% of the homemakers aged 48 and above showed no noteworthy interest in starting businesses.

Therefore, policymakers might benefit from exploring schemes that upskill younger homemakers in urban India with the requisite digital skills. Such skills, which complement the financial assistance offered by government interventions will allow homemakers to launch and expand their small businesses.

While the results of the aforementioned study were largely limited to homemakers in Tier-1 cities, various non-profit organizations are working towards imbibing digital skills among homemakers in rural India. For example, the Mann Deshi Foundation seeks to empower female entrepreneurs in the rural areas of Maharashtra and Karnataka. The organization aims to provide female micro-entrepreneurs with an enhanced skill set via courses in financial and digital literacy, agri-business training, basic computer programming, and other vocational skills, to successfully set up their businesses.

The foundation also uses a community radio in these areas to spread awareness of schemes launched by the government to promote entrepreneurship among women. This is particularly important given that only 1% of women participate in government schemes due to reduced awareness.

While several schemes have been launched by the government to promote entrepreneurship in the country, hardly any focus particularly on upskilling homemakers. Some exceptions like the Credit Linked Capital Subsidy Scheme (CLCSS), which aims to improve technology and mechanization in small-scale industries like coir and khadi production give preference to women entrepreneurs. Even though an upgradation in technology is a welcome step towards the introduction of modern skillsets, it cannot be equated with digital upskilling.

The 2022-23 Union Budget saw no mention of the CLCSS, and technology upgradation saw a massive slash of 75%. Contrarily, there was an overall increase in the allotment for MSMEs. This suggests a unidimensional approach to the expansion of local small businesses, which promotes the growth of the local economy without introducing any schemes specifically for women and homemakers, who face additional domestic and societal challenges.

A large number of sectors in the economy remain heavily weighted against the employment of women. This was most recently exemplified by the State Bank of India’s (SBI) circular preventing women pregnant for more than 3-months from taking up jobs in the public bank until after delivery. In such scenarios, small businesses run from home provide some respite. However, in a primarily digital world with facilities like online banking and transactions essential to running businesses, homemakers must be provided skill development in digital services that can uplift them to professionals. Though such initiatives cannot completely eradicate the gender gap in the economy, it is a promising step towards achieving some semblance of economic equality.

Despite some progress in this sphere, social and domestic constraints surrounding homemakers remain a harsh reality in India. As of 2018, only nine countries in the world, including Syria and Iraq, have a lower working population of women than India, with most homemakers primarily running households. India’s Female Labour Force Participation Rate (FLFPR) fell to 16.1% in 2020 from an earlier 20.5% in 2019. The pandemic was a significant contributor to the decline in the FLFPR, particularly with an increase in household duties for women. In 2020, 43% of female small-business owners in urban areas reported a drop in productivity because of household distractions, as per a report by Bain and Company.

The central government has launched various initiatives to aid the economic recovery and growth of MSMEs in India, such as the Emergency Credit Line Guarantee Scheme (ECLGS). This scheme enables small and medium business owners to extend emergency credit facilities with banks to stabilize their businesses post covid-induced lockdowns.

What remains missing from a majority of such schemes is a recognition of the additional burden of the family and household duties that homemakers face. Not just homemakers, even general schemes to specifically assist women-led business remain absent. This highlights a prominent gap in policymaking since almost 73% of female-owned enterprises were negatively affected by the pandemic, and 20% are on the verge of shutting down, as per the same report. Thus, recognition of this uniquely female experience might prove to be useful in future policies aimed towards upskilling.

Jaidev Pant is a third-year student of Psychology and Media at Ashoka University. He is interested in popular culture and its intersections with politics, gender, and behavior.

Picture Credits: Mexy Xavier

We publish all articles under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noderivatives license. This means any news organisation, blog, website, newspaper or newsletter can republish our pieces for free, provided they attribute the original source (OpenAxis).