2021 marks a decade since Dr. Harish Hande was awarded the Ramon Magsaysay for social entrepreneurship. It also marks ten years since he started SELCO’s first Integrated Energy Centre at busy junctions across India. Excerpt from an Open Axis interview series, focussed on how path-breaking Indians are responding to the climate change challenge.

Q: Can you please tell us about an innovative project you led in 2021?

A: The projects we did this year mostly were on the health side, because of the COVID-19 pandemic. So, many of the public health centres in our country got powered by solar, leading to better reliability of electricity for both ventilators and oxygen, and maternal labour rooms. So, I would say those would be the most impactful programs we would have done this year.

Q: In September 2021, SELCO partnered with the Union Ministry of Health, to provide solar health facilities in ten districts across five states. What is your vision for this project?

A: My vision is, the ten districts are just the first pilot phase. Hopefully, with the collaboration between the Government of India, SELCO, and the Government of Odisha, Karnataka, Meghalaya, and Manipur, would lead to at least twenty to twenty-two thousand public health centres in our country with reliable solar power. Moving the needle of sustainability between health and energy. That would lead to more number of centres across the country. So becoming a kind of an example for other countries to follow. Ultimately, we make sure that the 1.3 billion people of our country are able to access health in the most affordable and sustainable manner. So, this project is towards that goal.

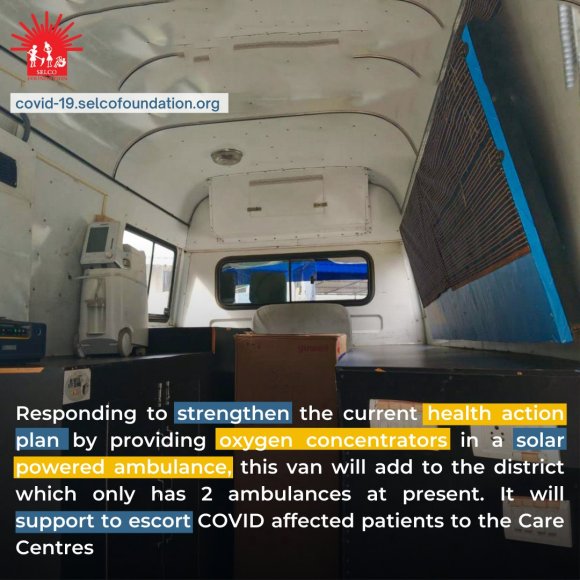

(Note: Over the last one year in a range of other COVID-19 support, the Kumbharapada potters of Puri (Kumbharapada means the place the potters stay, in Odia) who made pots for devotees at the Jagannath Temple were stuck with zero-income during lockdowns. From ration kits for the most vulnerable among them and consultations with households on better market linkage, SELCO’s ground teams are also said to have offered quick turnaround to space constraint and resource crunch issues by making ambulances go solar, creating mobile swab vans for testing on the street in Odisha and in areas where there are no public health centres, getting solar hospitals up and running in less than a month.)

Q: Reports say the pandemic has increased inequality and challenges for the poor. What have been some of your observations in the field?

A: Surely, it has. Not only have the poor lost their opportunities, but they also do not have access (Says number one, as if counting mentally, making point by point) first to technology and have no options to work from home. While many of the people who have had the option to work from home, not only got their salaries, but also have reduced their expenses by not going to restaurants or movie theatres. Which in fact led to an increase in their savings. However, for the poor, it has been precisely the opposite because of the dire strait. Many of the poor had to sell their assets like their land or jewelry, because of the hunger in their house. So it has definitely led to an increased disparity. That is what concerns a lot of us more than just the pandemic — How do you make sure the 200 million Indians who went into poverty in the last one year, do have an adequate and equitable chance to come forward?

Q: How do you see the connection between poverty reduction and sustainable energy?

A: The biggest connect is, if we have to decrease poverty in our country, we have to have people get access to better health, better education, and better livelihoods. The most economical and socially sustainable programs are the ones using sustainable energy as a catalyst, to create appropriate access to health to the remotest families and provide ample livelihood opportunities. So that’s where the link is between poverty reduction, sustainability, and climate. How do we make the poor resilient to the climate crisis? A lot of the poor are poor because they don’t have access to essential services. Many of them are poor because of the onslaught of climate change that is happening day in and day out in their particular fields. That is where sustainable energy becomes a catalyst.

Q: You have always emphasised the difference between intellectual poverty and financial poverty. Could you please tell our readers more about this difference?

A: If you look at the farmers who have been farming for many years, who might be poor, but a lot of people do not consider them as Agri-experts. Because our expertise is defined on the education levels that everybody gets. But not on the experience somebody goes into. So a paddy farmer is much more of an expert than an agricultural professor in many ways. A car mechanic, in many ways, is much better than a mechanical engineer per se.

So how do we define what expertise is in this country – it all depends on the paper education we all get. It is high time we went away from this whole concept of paper degrees and education and where somebody has qualified from. So, I think we need to get away from that competitive race which is not leading our country anywhere. So, how do we give honour and respect to people who actually have the experience, like the cotton farmer, the shop guy, the guy who does the ironing of clothes, et cetera? They are all experts. So…

Q: I wanted to ask you about your collaboration with the Karnataka Vikas Grameena Bank. Out of 615 branches, 170 of them in remote rural areas run on solar power since 2018. Could you please tell us the response of the people who visited the bank and work there?

A: One of the biggest challenges for people at the bank branches who work in the remotest areas is the unreliability of power, which actually leads to lack of linkages to the central database, providing loans to the poor who come to the banks. And number three, the uncomfortableness in the space, for the employees of the bankers, to actually stay there. And also save what was an extra burden on the bank, to provide inverters and diesel generators to these 170.

So they came up along with some colleagues at SELCO, with an innovative solution to provide decentralized solar systems to these banks, leading them to becoming very reliable and making services to the poor accessible. So that the poor did not have to come back again and again, making sure that their cost of transaction with the bank was reduced. Because, many a time, they would go to the bank and there is no power. So I think it is more the well-being of the staff, the reliability increased, there’s better disbursement of loans, leading to fewer hassles for the people and the clients that were coming to these 170 branches.

Q: Could you tell us how the response has changed over the years?

A: I think not much. Because after that, COVID hit, because of which, the banking sector in the country itself has gone down. But I would say Karnataka Vikas Grameena bank (KVGB) has been innovative right from, not 2018 — but they started working in this from 1995. So they are a pioneering bank who started this whole concept approximately twenty-six years ago. So I would say it’s more than just 2018, and unfortunately, the success of KVGB bank is not very much publicized in India, though it is more known outside the country than in India. It was also the first bank in the world to finance solar, to its end users.

Q: It has been ten years since SELCO’s first integrated centre was set up. Could you please tell our readers more about what one such centre does?

A: So the concept of IEC – The Integrated Energy Centre (IEC) came up many years ago, saying that rather than the poor buying the solar panels, is there a way that they could rent out the services per se, right? So we put up IECs in front of temples, churches, mosques, and busier places, where when people stay there, want to go and see the god, takes about five or six hours, so you put your cellphone there and the cellphone gets charged, and there’s a solar water purification system that actually leads to, rather than buying 10 rupees of clean water somewhere, they get it for one rupee. So these are services that integrate energy centres, so you create livelihoods. In the evening, the flower shop owners can rent out the lights and give them back at 10 p.m. In there, there is actually a refrigerator in which the flower pluckers can keep the flowers overnight if they have not been sold.

So how do you create these livelihood centers run by solar, provide essential services to the poor in and around that community so that was the concept of the Integrated Energy Centre. Which could be done in these large floating population areas, whether it is the bus stand or the local markets that used to take place on Thursdays or Wednesdays. That’s IEC…

Q: So is it like a module that can change later to other needs?

A: Yes, for instance, it can become a disaster room area, after floods. Photostat centre, think any services. It can be turned into a maternity labour room in 24 hours.

Q: Like the Covid hospital you built?

A: Yes, a hospital can be built in 14-21 days, that’s the beauty of solar, you can get it when you need it.

Q: How is your organization, SELCO’s work, aligned with the global discussion at the Glasgow CoP26 Climate Change conference?

A: I think (quiet for a moment, nods head and disagrees) I’m not sure it is linked, it may be linked but overall, countries that are contributing to greenhouse gases for so many years have to take more responsibility. We are pushing that India can be an R&D centre for the poor to be sustainable. That’s what SELCO is pushing for development, sustainability, and making the poor climate-resilient, using India as an R&D centre, in a manner that the poor Africans, Latin Americans, as well as Southeast Asians could then replicate what India is doing. Linked to climate change, linked to CoP26. But I think CoP 26 is still not grounded — it still talks about a lot of things in the air.

India is doing a lot more than just creating a grid. India is looking at the health-energy nexus, livelihood-energy nexus, education-energy nexus, gender-energy nexus. It is much more than just providing a solar grid. India is also doing a lot in the agricultural space, animal-husbandry space, resilient micro-business space. There are individual programs happening in different parts of the country, trying their best to make sure that the poor of this country are climate-resilient in terms of getting access to essential services like health, education, and livelihoods.

So I think it is just more than from the supply side that one needs to look at. It is not just about the solar grid. We need to look at it from a demand perspective. I think there are programs in India doing much more than just what the COP 26 is telling, it is more than that.

How access to solar impacts girls and women run home businesses like sewing.

SELCO’s Integrated Energy Centre, a space to run businesses powered by solar energy.

Q: India plans to put forth its One Sun One World One Grid (OSOWOG) idea at the Glasgow Summit. India aims to have a global solar grid. Since you have been in this sector for many years, do you think this will work?

A: I would break it into two parts. I think it’s about using the sun, as one source, and the grid need not be one grid per se, but individual people using their own way to do solar. Whether I need a smaller solar panel, he or she or a factory needs a larger solar panel, so, as long as we have one sustainable source, that is equivalent to having one grid, but having it in a decentralized fashion is what I would push for. Because if I have to look at a blacksmith who needs a smaller solar panel, while a silk weaver who needs a different solar panel per se, but they all are using solar energy to provide for their needs, I do not need to connect them by wires. It is like a little more modified way of thinking of mobile and telephones, for example. For example, no wires are connected, but communications are one. So I would push that agenda forward, saying that there is one source: the sun, but very different ways of reaching it out.

In Devanahalli, Karnataka, under solar-powered lights, mulberry silk production management.

A blacksmith using solar energy in Assam.

Q: How can governments or communities change their attitude to decentralised renewable energy?

A: I think more than the government; individual citizens need to change. We have relied too much saying that the government has to do it. I think what are the individual citizens in this country, especially the middle class and upper-middle-class, they are the biggest polluters, they need to change. They need to be more sustainable rather than living on the subsidies of the poor. I think it is high time that the middle class and above class took responsibility for our country or for that matter any country, and ask what is our goal of sustainability?

The wastage, I think, for example, we should collect garbage from everybody’s house, and they need to pay according to the weight of the garbage they have created. I mean, in a decentralized fashion, pay for what you are doing. You might get water in this Bisleri, but the poor have to pay for the disposal of your bottle.

And that’s exactly why unless every citizen of any country takes responsibility and that can only happen in a very decentralized fashion, where you create decentralization of decision-making and democratization. And one of these solutions is distributed renewable energy. So, you break away from these centralized power structures, including electricity.

Q: In your Linkedin profile, you have mentioned how you spent 3-5 years trying to get a Masters and a PhD, that you are not sure has come to any use. What kind of courses need to exist in the college curriculum to talk about renewable energy?

A: The first thing is that we should stop the whole concept of exams. Exams make no sense. What are you examining against?

So I would say, how do you create a program or a project-based or experienced-based education for kids, rather than examination. Do theoretical, theoretical is as important as practical, but do theory on the field. I mean, if somebody wants to study rice paddy, go and do paddy field work for like six months. If you want to study a street vendor, be a street vendor for a year, along with other street vendors. As we study more, we become less useful to society. So, I think our expertise is a fallacy and an absolute waste of time. I would push the youngsters to be on the field all the time, on the roads, on top of the mountains and start doing it rather than writing about it.

I mean, writing is the easiest. I mean Facebook, Twitter, and all that. I mean, tell me how many farmers actually go – I have grown X number of sugarcane. I think it’s a very wrong way of publicizing oneself. So my only question, when people, professors ask me or tell me, or send me their resume, tell me how many people got impacted by one paper that you wrote.

Q: What do you think India is doing right in decentralising energy to end poverty?

A: We are a vibrant democracy. I can actually go to any rural part of this country and work with local banks, local civil societies, local NGOs, local entrepreneurs and enterprises. I think it’s not about what India is doing right or wrong. And I would say, as a country, we offer to the world, enormous opportunities for innovation, right from dry areas of Raichur to the wet areas of Meghalaya, to the terrains of Manipur, to the flat lines of Gujarat to the innovators of enormous options. That is why India is an R&D hub for the world in many ways.

I think that is where I would say citizens and many of the educational universities are not getting it right. We are creating a xerox of all students coming out. We are not teaching the kids to be taking risks, taking to be highly innovative and fail. If India has to get it right, the citizens and the academic institutions need to change and celebrate failures, not one or two successes.

SELCO Pvt. Ltd. and North Eastern Karnataka Road Transport Corporation (NEKRTC) create a mobile restroom for women using an old scrapped bus in early 2021. NEKRTC since July 2021 has become KKRTC.

Note: The interview was done via a video conferencing tool on October 24, 2021. The order of the questions in this published version has been changed for better readability. Mr. Hande’s responses have not been altered, except the last two have been shortened for brevity. You can read more about his work here.

(Cover image credit: SELCO Foundation)

Cefil is a student of Mathematics and Environmental Studies at Ashoka University.

We publish all articles under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives license. This means any news organisation, blog, website, newspaper or newsletter can republish our pieces for free, provided they attribute the original source (OpenAxis).