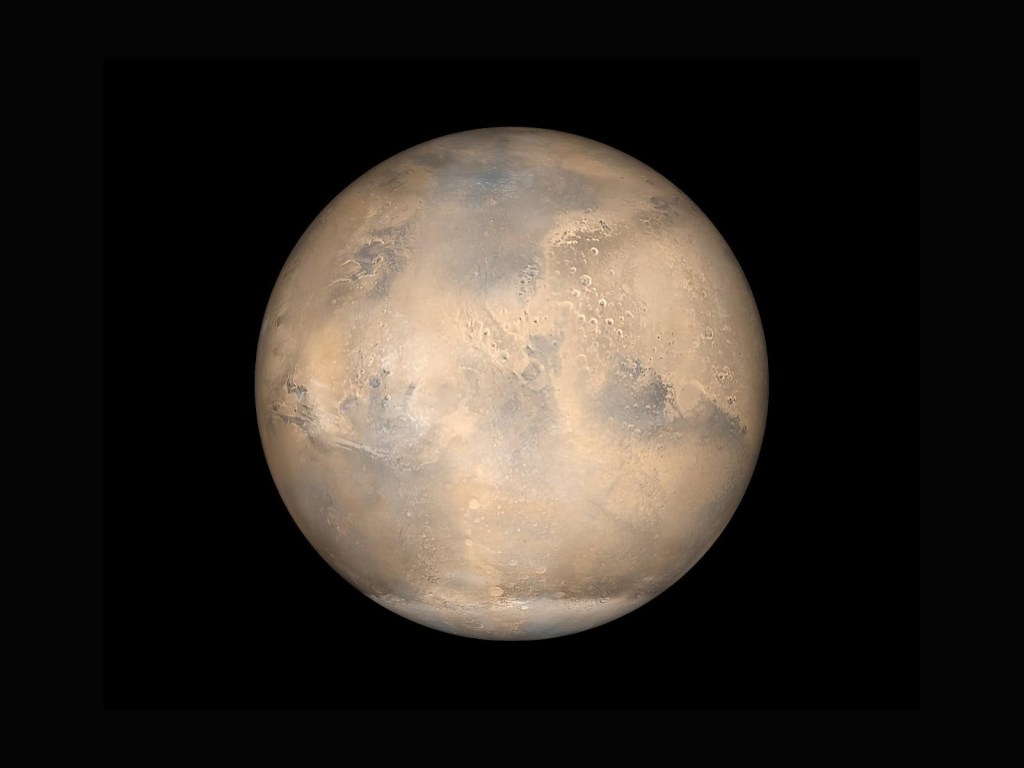

The mysterious disappearance of Mars’ ocean witnessed a major breakthrough in the past week – it might have never been lost at all. A recent NASA-backed study found that between 30 to 99 percent of the planet’s water is likely held within its crust in the form of hydrated minerals. While the extraction of water from these minerals may not be an easy feat, the study has gathered substantial traction at a time when humanity is looking to Mars like never before. Why are human beings obsessed with colonizing Mars – and what does this obsession represent?

The desire to explore Mars initially stemmed from a curiosity to enhance knowledge about the conditions that lead to life on a planet. It is also studied to understand how critical shifts in climate fundamentally alter planets. Recently, though, the paramount motivation to explore the planet is rooted in the objective of establishing an interplanetary human civilization – as a crucial safeguard against mass-extinction.

The obsession with colonizing Mars is a product of several factors. One argument holds that only a space-faring human civilization faces the best odds of survival. This perspective is closely linked to the fear of death and the desire for “immortality” which motivates sending humans to other worlds. Moreover, a “biological motive(s)” with respect to the innate human desire for migration has been repeatedly suggested to substantiate extra-terrestrial prospects for the human race. Additionally, the romanticization of establishing an interplanetary existence for human beings also arises from optimistic perspectives of establishing a “utopia”. Setting up a space-faring civilization is expected to unify humanity and positively impact perspectives on socio-political and economic systems to finally create an “ideal” society.

As alluring as these reasons may be, they are not grounded in reality – especially given the glaring gaps in scientific knowledge about how to establish self-sustaining human life on Mars. The argument that only colonizing Mars, and other planets will significantly improve the chance of human survival can be countered by arguing that sending humans to other worlds may not prove to be safer beyond a probability analysis. Attempting to address crises on Earth – such as the climate emergency – may increase the probability of human survival as well. The prospect of reaching Mars can disrupt efforts to find possible solutions to problems on Earth.

Secondly, it is important to acknowledge that the idea of human progression is one that is culturally propagated. Just as human beings have historically shown tendencies to migrate, they have also displayed the desire to settle down. Justifying colonization of other planets on this basis ignores the fetishization of space travel, that equates space exploration with technological advancement and national power.

Thirdly, notions of a utopian human existence on faraway planets are naïve. The connotations of the usage of the word “colonization” elicits references to intergenerational torture unleashed at the cost of building “moral” and “civilized” societies. The modern interaction between “colonization” of planets and the advent of large-scale capitalism is bound to have similar consequences. Though human activities in space are governed by the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, which posits that international law applies in outer space, the moon and other celestial bodies, the ambiguities in its laws allows corporate entities to circumvent its clauses.

This came to life in the case of SpaceX, a private company based in the United States that designs and manufactures rockets and spacecrafts. The company has declared that the services of one of its products will not fall under the jurisdiction of any Earth-based government; in addition, Earth-based governments will also agree to recognize Mars as a free planet. This position becomes more dubious when analyzing SpaceX’s CEO, Elon Musk’s, claim that “loans” and “jobs” will be made available for those unable to pay for the exorbitant trip across space to sustain their life on Mars; essentially representing an interplanetary repackaging of indentured servitude. Hence, given the current state of space legislation, it will not be anytime soon that economic and social equality will be ensured for a space-faring civilization – completely shattering any possibility of “utopia” on Mars.

The colonization of Mars, consequently, also raises important moral questions – particularly about how a Martian society would operate. A new approach suggests that once human beings arrive at Mars, they should disconnect from their Earthly relatives. This “liberation” perspective implies that once permanent human settlers arrive at Mars, they should relinquish their planetary citizenship for Earth – instead adopting Martian citizenship. From that point on, the Martians should be left to their own devices. Any entities – governmental, non-governmental – must not engage with the economics, politics, or culture of this society. While scientific exploration by Earth’s citizens can continue on Mars, sharing research and information should only take place to achieve medical or educational goals. Most importantly, the citizens of Earth must not make any demands for Martian resources.

The idea behind this position is simple – in order to develop a Martian extension of human civilization, it must be allowed to freely determine its fate, just as human beings did on Earth. Often the mission to establish human existence on Mars is projected as a “moral” position by governments and businessmen, in which case the liberation approach is the most principled execution of this goal. The reason why this idea doesn’t sit well with human society – and probably never will – is because colonizing Mars is, inherently, a selfish, human fantasy. This fantasy emerges from the desire to possess and profit – either in the form of capital or nationalist feats, or both. It is impossible to isolate the race to establish human settlements on different planets from geopolitical, social and economic processes existing on Earth; the maniacal pursuit of Mars is about scientific triumph as much as it is about a show of power.

The obsession to populate Mars, hence, represents the manifestation of the worst in humanity – never-ending curiosity coupled with little regard for ethical, sociopolitical, or economic consequences of the same. Instead of addressing the glaring issues that currently exist on Earth, there are strong desires to “advance” to the perceived next stage of human existence. While it can be debated whether occupying other planets will objectively be beneficial, the only thing that becomes painfully clear is that humanity is preparing to leap from one ill-fated land to the next – with little awareness or regard for the problems it will inevitably carry to the new worlds it explores.

Aarohi Sharma is a Psychology student at Ashoka University. Her academic interests primarily focus on the intersection of politics and psychology in society.

We publish all articles under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noderivatives license. This means any news organisation, blog, website, newspaper or newsletter can republish our pieces for free, provided they attribute the original source (OpenAxis).