“War makes for bitter men. Heartless and savage men”, said Ethiopia’s current Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed in his acceptance speech, while being conferred with the prestigious Nobel Peace Prize. Merely 18 months into his tenure, Ahmed received the Prize in 2019 for introducing sweeping reforms to undo the authoritarian legacy of his predecessors. He freed political prisoners, enhanced press freedoms, mediated regional conflicts in the Horn of Africa but most importantly, his historic rapprochement and resumption of diplomatic ties with longstanding rival and neighbor Eritrea is what fetched him the prize.

Fast forward to present day, the northern region of Tigray in Ethiopia is witnessing a gargantuan humanitarian crisis with 2.3 million people in need of urgent assistance. Surprisingly, Ethiopia’s Nobel Laureate and “Champion of Peace” is at the centre of this.

Ahmed’s intentions to “unify” Ethiopia by bolstering federal powers and mitigating regional autonomy caused uneasiness among Ethiopia’s ethnic groups, especially the Tigrayan Peoples’ Liberation Front (TPLF). TPLF, which was the dominant party in Ethiopia’s ruling coalition until Ahmed’s election in 2018, openly resisted by defying the government and conducting regional elections despite all elections being postponed because of coronavirus. At the behest of Ahmed’s retaliatory orders post elections, the Ethiopian National Defense Forces have carried out aerial bombardments, sexual violence, ethnic-based targeted attacks and large-scale looting in the region. The government-imposed lockdown and communications blackout in the region has massively affected internet and telecommunications access. Resultantly, the humanitarian aid agencies have been unable to reach the local population that is in dire need of assistance. Media seeking to gauge the extent of atrocities in Tigray has been denied permission. Additionally, journalists in Ethiopia have faced threats, been harassed and detained.

With his cardinal role in the Tigrayan pogroms, Ahmed is the latest entrant in the extensive list of controversial Nobel Laureates that have fetched incessant disrepute for the Peace Prize. Henry Kissinger won the Prize in 1973 for his efforts in Vietnam, despite his alleged ordering of a bombing raid in Hanoi while negotiating the ceasefire. Months into his Presidency, Barack Obama was awarded the prize in 2009 as an “anti-war” candidate in the hope that he would withdraw the United States from its violent commitments in the Middle-east. As it turned out, even though Obama shied away from active military-intervention, he indulged in covert drone-warfare and left an exceedingly controversial legacy in the region. Similarly, Aung San Suu Kyi was hailed as “an outstanding example of the power of the powerless” when she was awarded the Peace Prize in 1991 for her persistent efforts to democratize military-ruled Myanmar. However, in 2017 Suu Kyi disappointed her international supporters as Myanmar’s de-facto leader by not only refusing to condemn the genocide against the Rohingyas but also offering a defence for the army’s actions at the International Court of Justice.

So, why does the Nobel Committee have a tendency to pick unsuitable candidates recurrently? There is no single explanation to this. Yet, the solution lies in scrutinizing the process that is followed to declare the winner.

The decisive criteria for the prize are working towards fraternity between nations, abolition or reduction of standing armies and holding and promotion of congresses. The problem here lies in the ambiguity of these criteria. These are open to interpretation for the Nobel committee. Suu Kyi was an intelligent, well-read, articulate and vocal leader who was a perfect symbol of democracy, making her a seemingly perfect candidate for the Prize. To most people, Abiy Ahmed’s vision of medemer, an Amharic word connoting ‘strength through diversity’, sounded alluring and perhaps evoked the hope that he would work towards quelling ethnic strife in Ethiopia. Many argue that Obama’s initial commitment to discontinuing with George Bush’s brutal Middle-Eastern policies is what earned him the Nobel. It is undoubtedly a herculean task to bring about rapid change internationally but making a few impassioned speeches to raise awareness and elucidating on one’s vision without actually having made substantially quantifiable progress could also be considered as “working” towards the aforementioned goals. Therefore, tangible achievements inevitably take a backseat in the selection process.

Secondly, despite the Nobel Prize’s global significance and far-reaching political implications, the selection process is appallingly exclusive. The award is administered by the Norwegian Parliament through a committee of 5 Norwegian individuals that are understandably oblivious to the deeply entrenched political narratives in different parts of the world as the examples of Myanmar and Ethiopia vividly suggest. Owing to the complex narratives of ethnic rivalries in the country, Suu Kyi’s vision of a democratic Myanmar was bound to blatantly exclude the long-persecuted Rohingyas. Correspondingly, Ethiopia’s rapprochement with Eritrea had primarily to do with Ahmed’s and Eritrean President Afwerki’s common foe, the TPLF, as is suggested by the massacring of numerous civilians in Tigray by Eritrean soldiers. A comprehensive understanding of the subtleties of politics in these regions could have helped avert the handing over one of the most significant prizes in the world to these personalities that have ceased to stay peaceful.

Lastly, strict rules of secrecy that disallow revealing the details of each round of consideration for 50 years should be removed. It is imperative to transform the selection process by incorporating transparency to ensure the non-existence of any biases or prejudices and to enhance accountability. The lack of transparency makes the process susceptible to international pressures and the furthering of selective global narratives as can be gauged from China’s warning to Oslo against granting the Peace Prize to protesters in Hong Kong. It is also speculated that Barack Obama’s surprise win in 2009 was an international rally to mend America’s international standing that was at the nadir after Bush’s tenure. This unavoidably and unfairly takes away this significant honor from other more deserving personalities.

Nobel laureates are meant to be harbingers of peace in this excruciatingly peaceless world that we inhabit. In order to set healthy precedents, the onus is on the Nobel Peace Committee to award this significant honour only to the ones that can leave a legacy for future generations to follow, and currently it is miserably failing at that.

Saaransh Mishra is a graduate in Political Science and International Affairs. He is deeply fascinated by geopolitics, human rights, the media and wishes to pursue a career in the confluence of these fields. In his spare time, he watches, plays, discusses sports and loves listening to Indian fusion classical music.

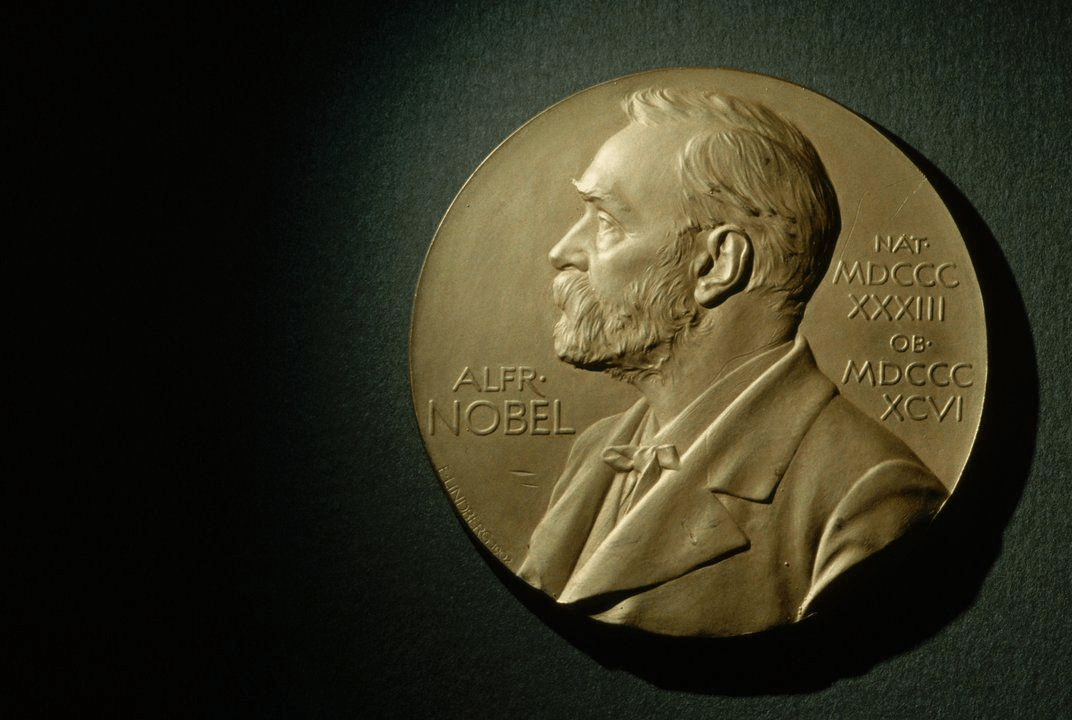

Picture Credits: Wallpaper Cave

We publish all articles under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noderivatives license. This means any news organisation, blog, website, newspaper or newsletter can republish our pieces for free, provided they attribute the original source (OpenAxis).