The recent coup orchestrated by the Tatmadaw (military) in Myanmar has attracted deep concerns and condemnation, with countries calling it a “serious blow to democracy.” In the aftermath, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing is in control of the country, civilian leaders have been detained, the internet has been shut down and a state of emergency has been imposed for a year.

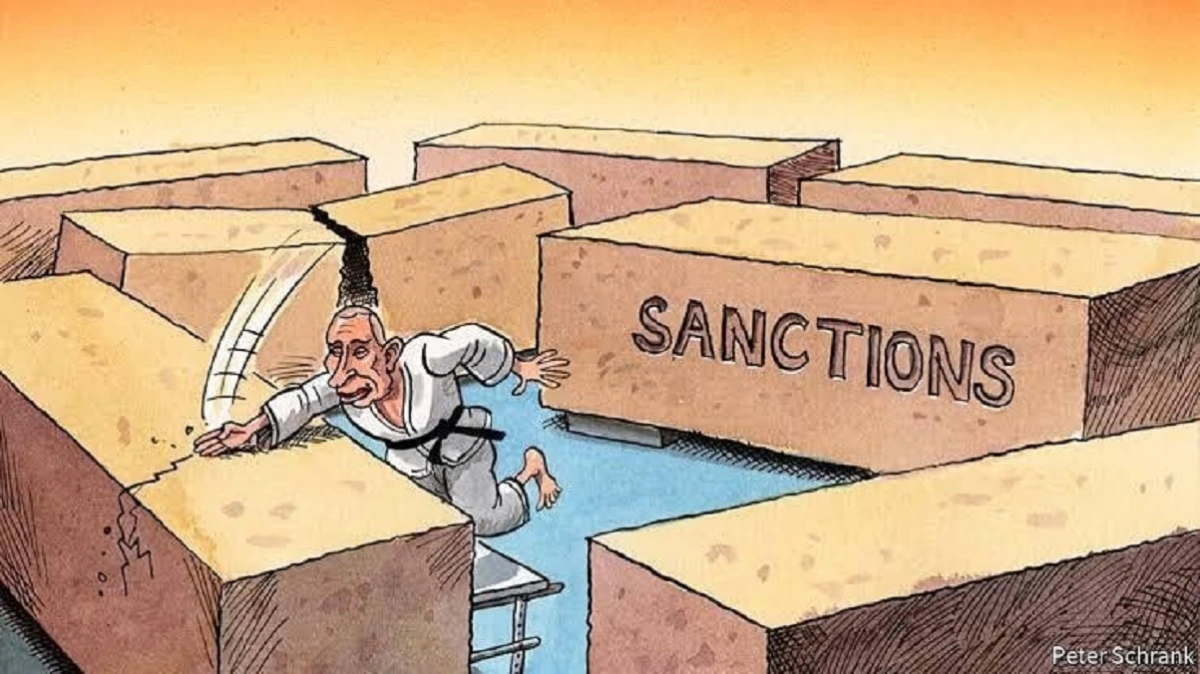

In alignment with the US’s long standing policy against authoritarian regimes, President Joe Biden has threatened to re-impose sanctions on Myanmar that had progressively been rolled back by the Obama administration following the initiation of democratic reforms in 2011. This threat is congruent with the popularly hailed western narrative of Myanmar being a “sanctions success” story. However, a closer look at Myanmar as well as other sanctioned regimes highlights the ineffectiveness of sanctions in attaining desired objectives. Additionally, sanctions have also often exacerbated pre-existing human rights situations, leading to more hardships for the people while regimes have stayed intact.

Economic sanctions are instruments of statecraft where there is a use or threat of use of economic capacity by a state or an international organization against another state or group of states to alter behaviors. These behaviors range from proliferation of nuclear weapons, compromising human rights, harboring terrorism, engagement in armed aggression and replacement of incumbent repressive governments. The economic threat is imposed mostly through means such as arms embargoes, asset freezes, trade restrictions, visa and travel bans besides others.

The rational logic behind sanctions is that since actors are concerned about economic outcomes, they would be compelled to commit towards certain behavioral norms as a result of expression of official displeasure through sanctions. Yet surprisingly, a landmark study spearheaded by economist Gary Clyde Hufbauer showed the success rate of sanctions at a meagre 34% in the 116 examined cases since 1914. A further reanalysis of the same data by political scientist Robert Pape pins the figure at an abysmal 4%.

The United States first imposed sanctions against Myanmar in 1988 to curb human rights abuses facilitated by the military regime and more sanctions were added via legislations and executive orders over the following decades. Nevertheless, sanctions failed to bolster the Myanmar government’s scores on measures of civil liberties and political rights from 1990-2011. The government continued the usage of torture, murder and disappearance to clampdown on political dissent and recurrent repression of ethnic minorities throughout the 1990s and 2000s. Extensive sanctions did not prevent India and Pakistan from acquiring nuclear capabilities, nor did sanctions against Russia prevent excesses in Ukraine or the undemocratic annexation of Crimea. Similarly, North Korea had conducted six nuclear tests despite the imposition of multilateral economic sanctions by the US in 2002 and the United Nations Security Council in 2006 with respect to the pursuance of its nuclear program.

Sanctions primarily fail due to the globalized world we live in. When sanctions lead to closure of one market, targeted nations have the liberty to shift their economic focus to other markets and trading partners in order to maintain a respectable volume of trade. The big players like the US or the EU imposing sanctions is treated as an opportunity by other emerging yet major economies like India, China, South Korea. The differences in foreign policy among countries has an instrumental role to play in the survival of sanctioned economies. For example, China’s long-term foreign policy of non-interference in the internal affairs of another state has been essential to the rise of China as Myanmar’s dominant economic ally since sanctions were imposed in the 1980s. World Bank figures indicate that Myanmar does $5.5 billion worth of trade with China each year, constituting 33% of all imports and exports. In stark contrast, the US foreign policy’s incessant emphasis on the spread of democracy has meant that the US is not in the country’s top 5 trading partners. China has also continued to have sizable economic ties with heavily-sanctioned North Korea, with bilateral trade increasing ten-fold between 2000-2015, reaching a peak in 2014 at $6.86 billion.

Barring effectiveness, precedents such as Iraq, North Korea and Iran also bear testimony to the gargantuan humanitarian crises that such sanctions trigger. Owing to prior reliance on imports for two-thirds of its food supply, the punitive financial and trade embargo imposed on Iraq in 1990 due to the invasion of Kuwait led to a price-rise of basic commodities by an astonishing 1000 percent between 1990-1995. This resulted in a 150 per cent increase in infant mortality rate and at least 6,70,000 children under-five died due to impoverished conditions. Parallelly, the World Food Program estimates from 2019 show that approximately 43.4% (11 million) of the population in North Korea remains undernourished. The report states that the international trade restrictions only exacerbate the pre-existing food insecurity and malnutrition. Although Iranis cited as a sanctions-success story due to the signing of the Iran Nuclear Deal in 2015, the economic burden of these sanctions had already pushed 30% of the population into absolute poverty by 2017-2018. This segment of the population was estimated to be living on $1.08 a day. The Iranian Parliament’s Research Center also estimated that the sanctions-induced inflation will result in nearly 57 million Iranians living in poverty by March 2020.

Sanctions are regarded as an inexpensive and peaceful alternative to war, as a means of enforcing discipline and promoting peace. However, the accompanying human costs raise pertinent questions about their feasibility. In an interconnected world like ours, isolationist measures like unilateral or bilateral economic sanctions are bound to fail unless there is widespread international cooperation and consensus. However, distinct approaches to foreign policy have ensured the unattainability of such a consensus. Additionally, isolationist sanctions have inevitably pushed authoritarian regimes into the orbits of other similar regimes as demonstrated by China’s support for the Myanmar military as well as the North Korean government. Considering these consequences, there rises a need for reassessment of the usage of economic sanctions as a disciplinary instrument by the great powers.

Image Credits: The Economist

Saaransh Mishra is a graduate in Political Science and International Affairs. He is deeply fascinated by geopolitics, human rights, the media and wishes to pursue a career in the confluence of these fields. In his spare time, he watches, plays, discusses sports and loves listening to Indian fusion classical music.

We publish all articles under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noderivatives license. This means any news organisation, blog, website, newspaper or newsletter can republish our pieces for free, provided they attribute the original source (OpenAxis).