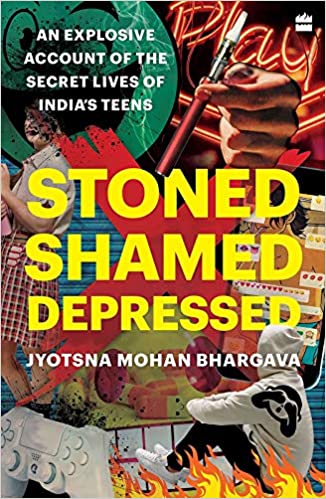

Stone, Shamed, Depressed: An Explosive Account of the Secret Lives of India’s Teens is a book that examines the lives of urban teens. Children as young as middle schoolers have started engaging in activities like social media usage, substance abuse, body-shaming, video gaming, sexual bullying and online-bullying. The author, journalist Jyotsna Mohan Bhargava, highlights the urgency of these matters. How does one deal with impressionable teenagers being exposed to virtues and vices that even adults have difficulty navigating? Why do these children, who have all possible resources and comforts at their disposal, engage in these activities? Here, I talk to the author about her observations and why she is worried.

Isha (I) – Starting with the topic of drugs, I always assumed that increased usage is a result of increasing freedom with age? Is that true or is there something else at play here?

Jyotsna (J) – I have heard lots of stories about college and there being choices available for every budget, but I find it fascinating the easy and casual usage in very young children, even in middle school. The difference in how they use it is that it isn’t recreational, it is an effort to fit in with their peers. It isn’t even a choice for many with the enormous pressure they are under to achieve ridiculous 100% cut-offs and very often you aren’t that student. As a society, we haven’t reexamined what we keep pushing our kids into. So kids are saying look, we’ll do it but doesn’t mean we’ll do it the right way. So many of them fall back on drugs to help stay awake and study constantly. A student told me that he started having marijuana at 13 and used it as an “experience enhancer” for movies. Why do you need that, why isn’t a movie enough for you? He said we’re all trying to fill a void, fill something. So there is a lot going on and it isn’t recreational for these kids.

I – In today’s environment where drugs have been vilified so much, I feel like this book could be used by someone to back their anti-drug stance. So how do you think this book fits into that whole conversation?

J – I have been very careful to not judge any of the stakeholders in the book and let others hopefully read between the lines and judge for themselves. Because it is not at all normal for 13 and 15-year-olds to be consuming marijuana and laced drugs. My attempt is to bring a mirror to our society because very often we don’t want to acknowledge that things happen, and if we don’t acknowledge if we don’t accept we’re never going to able to realize that some stuff is more important. We don’t really have a very cohesive drug policy or we’re not really looking at mental health when it comes to the young ones, so I think my book has been an attempt to actually bring issues out in the open so that we can accept and deal with them. If there is no acceptance there will never be any conversations and change.

I- So regarding policy, how do you think legalising marijuana or changing legal drinking age and such will affect this issue?

J- With everything, I think the buck stops with the family. Banning has never been the solution and I think really it all comes down to where you’re coming from. I could say that schools need better policies and sex education but the truth is we need to talk about it at home. I think there is an enormous amount of wealth being substituted for parents’ time and it is doing a lot of harm in the long run. Giving devices to these kids at the age of 6 and 7 and taking them back at the age of 13, it’s not working. It’s leading to aggression. Social media is a new toy for everyone and I think parents need to figure it out first and help kids harness it in a better way. We need to teach kids about cyber safety, or about how just because everyone is having drugs, doesn’t mean you should too. We need to normalise the existence of things that happen around us and say that this is no longer a western concept that everyone is smoking, drinking. One of the first people who reacted to the book was a gentleman on Twitter who said: “This is western bullshit”. This is precisely the reason I’ve written this book we’re still caught up in what should happen versus what is happening. If a child is using drugs, they need counselling and de-addiction centres, which is so against our values. So many children only have one question for me “How do we talk to our parents?” If someone is genuinely going through an issue whether it is mental health or sexual bullying, we need to deal with it accordingly and figure out what is and isn’t a mistake. If we aren’t willing to accept that a teenager hitting his parents or talking gangrape isn’t a mistake and other things are a mistake, we won’t realise that some issues do need deeper intervention. It all depends on how we acknowledge these issues.

I- Were a majority of your interviews based in Delhi NCR or how were they located?

J- No actually I have a lot from Bombay, Bangalore, Chennai, and Hyderabad. Each of these has its own problems. I think NCR is rocking it when it comes to drugs while there is more gadget addiction in Bangalore, gaming in Chennai. A college student in Delhi told me there is a difference in how drugs are used in Delhi versus in Bombay. In Bombay it’s something done by the older lot, you hear about celebs and substance abuse but it’s done and over with. In Delhi, it’s a production. All of these kids who were already on drugs in school, they are going into harder stuff in college and I don’t think there’s anybody who’s stopped them or had a conversation to tell them that you know when you’re lacing marijuana with something else, you’re reaching another level. They’ve never had these conversations and always had money.

I- So how would you say this works in Tier 2 And 3 cities?

J- The issues are different in Tier 2 cities. But anybody today who has a smartphone, even in rural and semi-rural areas is vulnerable. The genesis of it all is that smartphone. We’re pretty much the biggest market, I think some 839 million smartphone users by 2022, and a bulk of our population is young. You can do anything on that phone. I demarcated it as an urban book simply because in the very rural the issues are very different, the addiction is very different, it comes from the frustration of having to make ends meet, versus this society where everything is on a platter By that I also mean Tier 2 towns, they have a lot of money and are giving smartphones to kids. I don’t think you can demarcate too much because that vulgar language of gangrape in Mumbai you can also possibly hear it in Patna. In Tier 3, there’s a lot of gaming going on. As a country we’re aspirational and social media has opened up everybody to it. So kids who are getting botox at 15 are no different than the 9 or 10-year-old kid who has gone on the reality dance show on TV because the parents may be from Ludhiana or wherever, they’re equally aspirational. Many parents I spoke with find no issue when it comes to privacy, They say it’s part and parcel of the game. I am talking to you about cyber safety, but in a tier 3 city where you’ve given your child a phone and he’s gone to study in a school where you’ve never been perhaps, you’re not even equipped to deal with the knowledge he has.

I- Moving on to another topic you write about which is bullying, homophobia and body-shaming. These kids exist on social media where body-positivity and pro-LGBTQ+ stances are quite prominent. How do these kids exist in that space and still manage to act this way?

J- Again this comes back to the conditioning of our society. I can actually see that with 90% of people if a child goes up to their mother and father and says that I’ve been body shamed, I can actually see that the reaction is going to be, it’s okay, it’s a part of life, you’ll get over it. As a society, we don’t deal with anything that isn’t tangible. Even with the Sushant Singh Rajput incident, we circled around the issue for months. Finally, when we did come to mental health, we were talking about older people. We haven’t touched children. It’s enormous in the 15-20-year-olds. All kind of positivity starts with a society that says we may be traditional but that doesn’t mean it’s always correct that we need to move with the times and unfortunately I think that’s a long way from now.

I- A third topic you address is teenagers exploring their sexuality and having sex. How does one deal with this, at what age is it necessary to have a conversation about this?

J- My dilemma has been, how do you deal with consent by minors, when they have consensual intimate relationships and then have been asked to leave their schools and such. A lot of children are really sexually empowered and these conversations need to start very young, at 7 or 8 years according to some counsellors. Consent to me is a very big word with not adequate importance given to it by society. A lot of mothers have come up after some of these cases and said we’re teaching our boys respect but I think that’s tokenism. We need to go beyond it. A doctor made a lot of sense when he told me that in the last few years, we have been talking about how our girls are changing, how they are driving and working late doing everything. But we forgot to tell our boys to change as well. If they still remain where they were while girls are changing, we’re going to have this clash. There’s frustration in teenage girls as to why the onus is on them and we have done this to ourselves as a society. So consent is a very important word that we need to teach them.

I- In addition to body-positivity, social media is also urging women to embrace our sexuality. I am guessing that it’s targeting slightly older women but the narrative is also being embraced by younger girls. Since increasingly younger girls are trying to fit into this narrative of let me embrace my sexuality, how do you deal with that?

J- To be one of the girls, you have to let go of your virginity or you aren’t cool enough. Getting rid of it is like a badge of honour and very casual for 15, 16-year-olds. It really does come down to how comfortable a child is in their skin to be able to take this enormous onslaught of peer pressure. And knowledge is important when you’re, say, trying to date a boy and you send nudes over Snapchat and you think they will disappear after being seen, but somebody else has recorded it it’s in circulation. When no one speaking to them, they’re listening to their peers and going ahead so I think it boils down to really what those conversations you’re having at home, that communication channel has to always be open.

I find that even six months make a difference. If you keep pushing social media, say a child who gets in at 13 versus at 15 or at 8 versus at 12, I find that the child is evolving and learning more things. You can’t push beyond a point but that little bit of experience keeps adding up, that ability to scope things out react accordingly adds up.

I- How do you see these phenomena of drug usage and social media and such play out as these kids enter college and parents lose even more control. You have said that drug usage tends to increase in such cases, but what else changes?

J- I find that again it all depends on how solid your base is. Some things do change, for instance, people in their 20s are using social media for activism in unimaginable ways. Drugs may become a recreational activity more than before, but then mental health is escalating in the 20s. With the whole sex thing, I think kids are taking control of their lives you’re adults, so in that sense, it’s your life. Your parents have to make sure they’re around to hold hands be there if you want to talk.

In my interviews, this kept coming up about social media anonymity, how do you trust the world with bearing your body and soul? But we’ve all had our rebellion, unfortunately, it’s a lot to be on social media and living a public life. So the pressure to be somebody is more for your generation. We went to school and got bullied, got home and forgot about it until the next day. You go to school and get bullied and you come home you’re still getting bullied so its 24×7 now.

Isha is a student of Psychology, English and Media Studies at Ashoka University.

We publish all articles under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noderivatives license. This means any news organisation, blog, website, newspaper or newsletter can republish our pieces for free, provided they attribute the original source (OpenAxis).